Archaeologists have been captivated by the discovery of an ancient warrior’s grave in Suontaka Vesitorninmäki, Finland, first unearthed in 1968.

This Iron Age burial site held mysteries that baffled scientists for decades, offering both familiar artifacts and unexpected clues that hinted at a unique story.

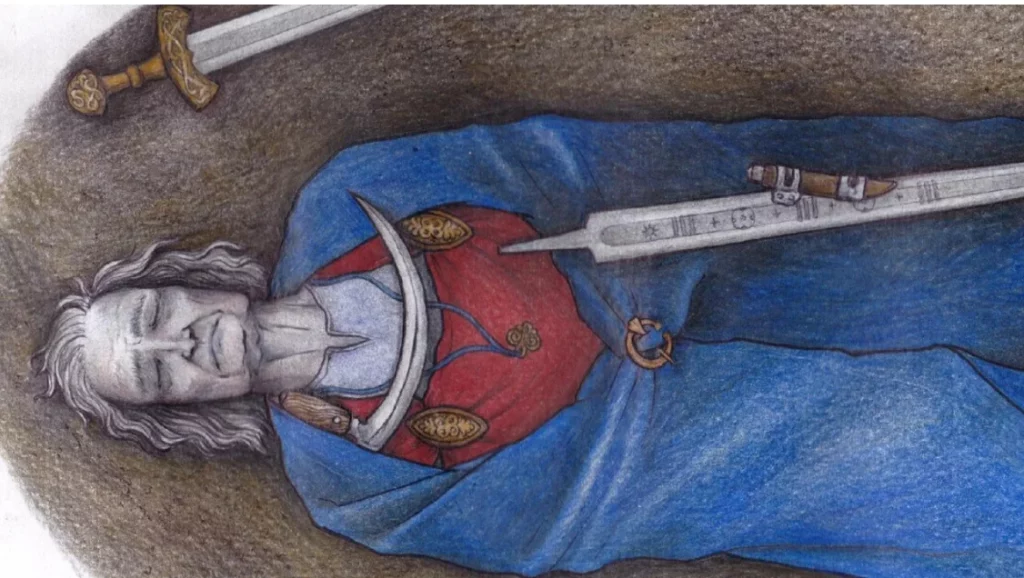

The items discovered in the grave seemed to carry both masculine and feminine symbolism, leaving researchers with unanswered questions about the individual’s identity and role within their community.

The burial contained objects typically associated with a high-status woman, such as jewelry and fragments of woolen clothing.

Among these feminine items were two swords—a feature that puzzled researchers.

Swords in medieval graves typically pointed to masculinity and warrior status, leading to a long-standing assumption that the grave either belonged to two people, one male and one female, or that it was evidence of a rare female warrior.

Yet, this interpretation never fully explained the grave’s unusual combination of artifacts.

Over time, technological advancements allowed scientists to revisit the remains with modern DNA analysis, shedding new light on the mystery.

Recent findings, published in the “European Journal of Archaeology”, revealed that the grave contained only one individual with a genetic profile that differed from the typical male or female pattern.

Analysis of the person’s DNA revealed an XXY karyotype, a condition known as Klinefelter syndrome, in which individuals are born with an extra X chromosome.

“Klinefelter syndrome is a common genetic condition in which people assigned male at birth (AMAB) have an additional X chromosome,” explains the Cleveland Clinic, adding that this condition can cause a variety of physical traits, including reduced muscle mass, less facial hair, and in some cases, enlarged breast tissue.

The study’s lead author, Ulla Moilanen, an archaeologist from the University of Turku, observed that “the buried individual seems to have been a highly respected member of their community.

They were laid in the grave on a soft feather blanket with valuable furs and objects,” indicating a revered social standing.

Researchers hypothesize that the individual may have held a unique place within the community, possibly as a leader or spiritual figure, and may not have been strictly regarded as male or female.

While the notion of non-binary identity might seem modern, the artifacts and symbols found in this grave suggest that gender identities outside the binary were not only present but also respected in early medieval Scandinavia.

“This burial has an unusual and strong mixture of feminine and masculine symbolism, and this might indicate that the individual was not strictly associated with either gender but instead something else,” Moilanen noted.

Experts in ancient DNA analysis, including paleogeneticists, have hailed the findings as groundbreaking.

Leszek Gardeła, an archaeologist with the National Museum of Denmark, expressed excitement, stating that the study demonstrated “early medieval societies had very nuanced approaches to and understandings of gender identities.”

The high-status burial has led researchers to an intriguing conclusion about the person’s identity, altering how we view gender roles in history.

Ultimately, the research challenges the long-held idea of an “ultramasculine environment” in early medieval Scandinavia.

The findings suggest that those with unique gender identities may have held respected positions and were valued members of their communities, providing a powerful shift in our understanding of gender fluidity through the ages.

Featured Image Credit: (Veronika Paschenko via University of Turku)